A Matter of the Heart

One cyclist’s story about how he underwent open-heart surgery and his incredible return bicycle racing.

Steve’s (name changed for anonymity) is a 55-year-old male who’s been riding and racing bicycles for 30 years. His story began in November 2018 with a mountain bike crash that launched him face-first into a rock garden, resulting in a severe concussion, multiple facial fractures, and 70-plus stitches to close the gash between his nose and upper lip. The recovery was prolonged as the concussion had impacted Steve more than initially thought. Steve’s wife noticed the difficulties he experienced following the crash.

COVID Lockdowns

Steve found himself impacted by the lockdowns. Initially he thought they were great because he often works from home, and he spent valuable time with his adult children. But like many during COVID, he spent less time cycling and gained 20 pounds, eventually becoming depressed, wondering where life was heading for his family.

November 2020

Fed up, Steve began working out again and quickly realized that his fitness was non-existent. He also noted feeling a “physical pressure” with cycling, jumping jacks, and burpees—he wrote this off as simply being “terribly out of shape” and assumed the journey back to peak fitness would be slower.

February 2021

While cycling on short rides around the neighborhood or local mountain biking, he noticed chest pressure and no power in the legs. Again, he wrote this off as “terrible fitness,” and figured the path to regaining any semblance of his fitness would be long. He continued riding, and the chest pressure persisted, constantly feeling like he needed to burp and figured, “It’s just gas.”

‘Twas a Terrible Day

In April 2021, while mountain biking in Virginia with his friend, whom he could easily stay with, but this day, he watched him ride away. His focus was narrowing; he stopped to vomit, and it felt like a death march riding home.

Could this be a Heart Attack?

Steve’s a typical cyclist who enjoys immense suffering. He wrote his fitness off as being “terribly out of shape.” But his intuition, that brain in his gut, told him something was off beyond fitness. Despite the pain, he continued to ride. In late April, he cycled around the neighborhood only to return after 6 miles because he felt horrible. Accepting that something was really wrong, he walked into the house, looked at his wife, and said, “I need to see the doctor; there’s something wrong with me.”

At his primary care doctor’s office, he explained that he was having chest pressure with harder cycling efforts. The doctor wisely performed an electrical cardiogram (ECG) on the spot and noticed “something abnormal,” so he sent him to the Cardiologist’s office for a stress test. Steve underwent a treadmill stress test at the Cardiology office and “tapped out” quickly at a heart rate of only 140 as he felt the chest pressure he experienced while cycling. A general feeling of malaise overcame him. With the abnormal ECG treadmill test, he underwent cardiac imaging, which was also abnormal and showed that he had myocardium (heart muscle) at risk. Steve was scheduled for a heart catheterization, like the one I underwent.

Cath Lab Day

It was May 4th, 2021, a day Steve wouldn’t forget. Steve’s uncle, an experienced physician’s assistant in a cardiology practice, advised what might happen. In the Cath lab, everything seemed be going as planned; the doctors were friendly, nice music was playing, and that a stent would be placed in his blocked coronary artery. Then he could return to riding and even racing; he knew another cyclist who had the same thing, and he got a heart stent and returned to racing with no problem. Steve knew he was in the right place. “Did you see that?” his cardiologist said. Steve’s heart sank, and an ominous feeling permeated the room. The heart catheterization was stopped, all lines were pulled out of his heart, and he returned to his hospital bed, demoralized.

Steve’s worst fears were coming alive as his Cardiologist entered the room and explained the extent of the damage – there was a 60% blockage in the left coronary artery, otherwise known as the “widow-maker,” and an 80% blockage down the left circumflex coronary artery. Those lesions could have been stented. However, it was the 99% blockage at a ‘T’ intersection of his right coronary artery that was unstentable and would require open-heart surgery, otherwise known as a coronary artery bypass graft or CABG. Steve was scheduled for surgery a week later, on May 12, 2021.

At The Hospital

Steve was terrified, aside from sedation for wisdom teeth extraction, he'd never undergone surgery. Even more, per the COVID protocols, only his wife was allowed to accompany him. Steve’s surgery was scheduled for 6 AM, the first of the day. Being rolled back for surgery is like taking off in an airplane. Usually, everything should go well; once you take off, it’s out of your hands. You start to realize that you’re surrendering to something outside of yourself, something that is, in fact, eternal. Steve remembers feeling like this as the anesthesiologist was injecting the medicine into his veins. He hoped for the best, knowing it was in God’s hands.

Steve’s surgery went long, and emerging from the anesthesia was difficult. He even required sedation to go back under, and they had his wife talk to him while he came out of it a second time. He spent 4 days recuperating in the hospital and was released to go home with good prospects for a full recovery.

A Second Chance

I’ve known Steve for years and eagerly followed his progress. Steve is lucky because his heart is strong and amazingly not damaged. Those first steps during recovery were tough, having to stop several times. Determined to finish this race so he could go to the next, Steve said, “How could I not?” He’d been given another chance! Steve’s journey has been arduous. He’s grateful for his incredible support system, for feeling normal, and for realizing life’s precious gift.

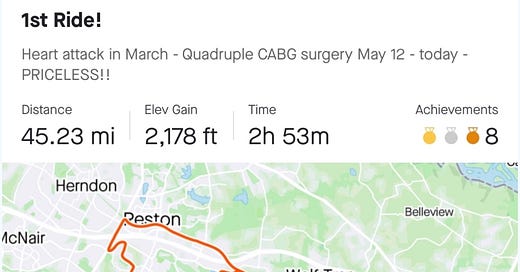

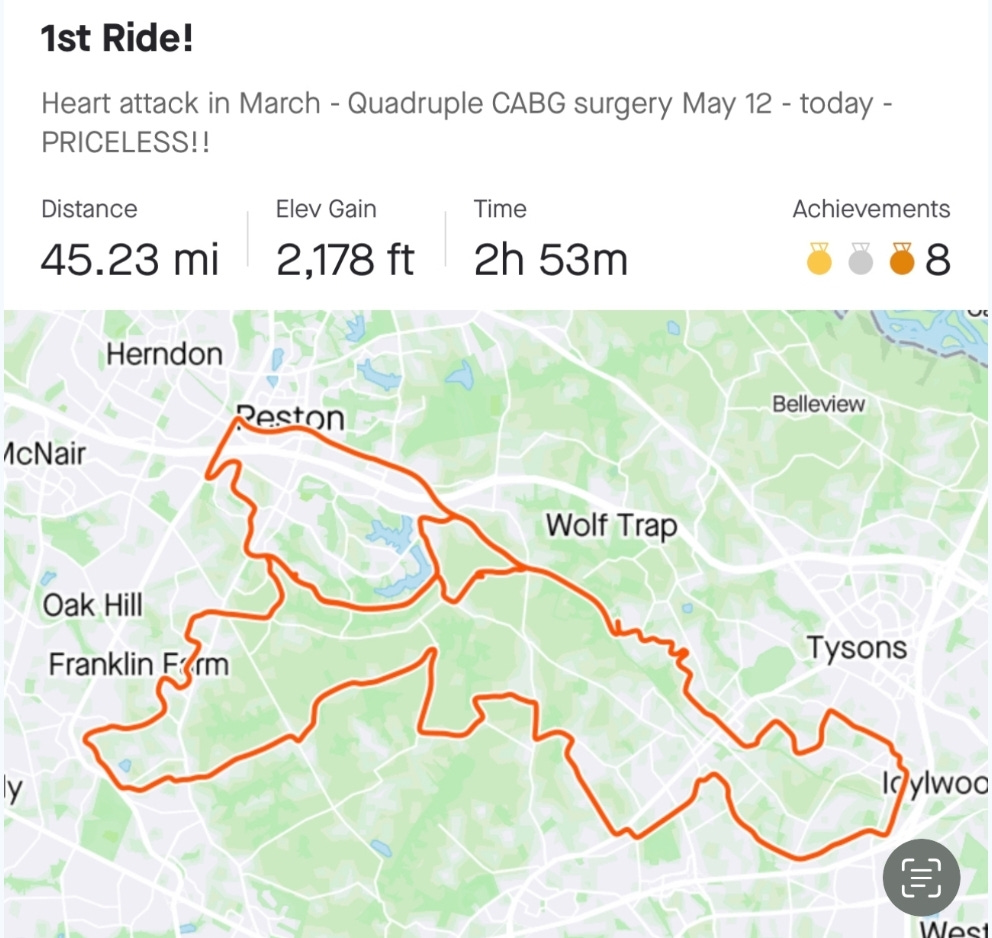

NOT The End of the Story

As a racer, Steve has always shown fierce determination and knows how to suffer on a bicycle. Cycling was his rehabilitation, not just for his heart but for his soul. Initially, it was slow, but he felt normal with time, almost like before. Three months later, Steve was riding outdoors again.

His fitness progressed, and after about 6 months, he told himself, “Why not? Why can’t I go back to competitive bicycle racing?” As Steve built endurance, he began feeling like his former self, and even better; given that he no longer had blocked coronary arteries.

When I heard that Steve was going to race bicycles again, it caught my attention. At first, I questioned his wisdom. I mean, he was just 6 months out from a surgeon sewing in new coronary vessels. One must realize that those coronary arteries are not arteries at all; they are the veins from Steve’s legs that are sewn over the diseased coronary arteries. In my 25 years of medicine, I’d never heard of someone getting a CABG returning to bicycle racing. I was able to find some studies where people who had CABG’s performed short bouts of high-intensity interval exercises, known as HIIT training. I’ve heard of people running a marathon at a leisurely pace post CABG. But bicycle racing is another animal; it involves riding at high intensities for hours at a time.

I asked my colleague, Dr. Phil Ovadia, a cardiothoracic surgeon, metabolic health specialist, and famous author of the book and podcast — Stay Off My Operating Table! He also said that he wasn’t aware of athletes returning to high level bicycle racing or running after a CABG, but he thinks that it’s possible. Dr. Ovadia says that it’s rare because cardiothoracic surgeons don’t often operate on high level athletes. In any case, Dr. Ovadia says that Steve’s case is impressive.

Steve has always been a “roller.” In cycling, this describes someone who can put the screws to you on a bike ride, i.e., making it hard. Steve is known for holding a high threshold on relatively flat roads for long periods. His doctor cleared him to resume normal exercise. The problem is that most doctors have no idea what “normal exercise” is for a competitive, hard-headed cyclist. We ride for hours at a time with maxed-out heart rates. So, how is Steve’s new heart going to handle this stress? Is 6 months even long enough? I had no idea, and I’m sure his cardiothoracic surgeon didn’t either. Most CABG patients don’t present with these types of questions.

A Long and Windy Road

Steve continued training, increasing the length of his rides to 2, 3, and 4 hours. His fitness was returning; after about 1-year post-CABG surgery, he was back riding at a good fitness level. Now, it was time to consider racing again. Steve wanted to race, as this is what he’s done for over 30 years. Once racing is in your blood, it’s always there. Undoubtedly Steve had been watching the Tour de France, itching to return to the peloton. Steve started high-intensity training and felt fine. His heart was working great, and he felt great. At his checkup, the surgeon told him he was fine and to keep doing what he was doing. It was working for him.

The First Race Back

Steve entered a couple of local criteriums and surprised himself by placing in the top five. Then he went on to win his state championship in the 55-plus category. Already, this is a fantastic result considering everything he’d been through. Fast forward to 2023, Steve aimed to race the Master’s nationals in Augusta, Georgia. Each year, the country’s best Masters cyclists compete for a national championship. It’s mostly about bragging rights, but hundreds race the event. Steve built a training program for the nationals.

At Augusta, Steve entered the 55 plus category in the road race and the criterium. August is the hottest month of the year in Georgia, and this makes the racing hard. The racing went fine, and Steve stayed with the pack, but ultimately dropped out like dozens of others. He had overtrained himself as his Strava fitness scores dropped from 109 to the 70s. All things aside, racing nationals confirmed he was in a good place to regain full fitness.

Thriving, Not Just Surviving

Steve’s story of having nearly died from a heart attack (and he came closer than you might imagine), then getting open-heart surgery, and finally returning to bike racing at the highest level for his age is simply incredible. He’s already planning for next year. Hopefully, this story will motivate others who are going through similar situations. The human body is resilient and simply amazing if you have the determination and will.