Cancer Claims 600,000 Lives Yearly: Time to Prioritize Prevention Over Treatment

Every year, more than 600,000 Americans die from cancer. If we live long enough, each and every one of us will have a cancer of some sort. This stark reality underscores the need for a national shift in thinking. We must prioritize prevention with the same urgency and investment we give to treatment. This means holding institutions like the National Institutes of Health (NIH) accountable for how our tax dollars are spent. It also means demanding transparency in clinical trial reporting, empowering individuals with the information they need to make informed decisions about their health.

It’s time we stop treating cancer like a lightning strike and start treating it like the slow-burning fire it often is—one that can be prevented, managed, and even extinguished before it ever takes hold. Late-stage detection and aggressive treatments come with high costs, not just financially, but in lives lost to the very therapies meant to save them. Meanwhile, prevention—through immune support, environmental awareness, and nutrition—remains tragically underfunded and underexplored.

The data is clear:

The recently released MAHA report notes an 88% increase in U.S. cancer incidence from 1990–2021, with the U.S. having the highest global cancer rates. Even more alarming, childhood cancer incidence has risen over 40% since 1975.

According to the report, the key Drivers of Cancer are:

Ultra-Processed Foods (UPFs): UPFs, which comprise nearly 70% of children’s diets, are associated with obesity, diabetes, and certain types of cancer due to their high levels of sugars, refined grains, and additives.

Chemical Exposures: Pesticides (e.g., glyphosate), food additives, and environmental toxins are flagged as potential carcinogens.

Sedentary Lifestyles: Lack of physical activity and excessive screen time (averaging 9 hours daily) contribute to obesity and chronic stress, which are risk factors for cancer.

Overmedicalization: namely, the overprescribing of medications and polypharmacy.

Radiology and Cancer Diagnoses

My discussions with my interventional radiology colleagues led me to ponder: why aren’t we directing more attention to cancer prevention?

Drawing from his experience as a radiologist, he noticed that once cancers are visible on a radiology exam, it’s often too late. However, by focusing on prevention, we have the potential to significantly reduce the incidence of late-stage cancers. The urgency of this issue cannot be overstated.

Monthly Prevention?

Why aren’t we advocating for a program that could be taken monthly or at some time interval to empower our immune system to identify cancer cells before they materialize? For example, many oncology doctors are known to fast for an extended period, at least once a year. We know that fasting has a positive effect on killing cells that are ready to die but won’t; these are called senescent cells. Are there vitamin protocols such as optimizing vitamins D and C to certain levels that could be preventative? Indeed, getting enough sunlight, maintaining good relationships, and practicing meditation have all been shown to optimize health.

Prevention is the Key

Prevention is often touted as the most effective strategy for reducing the cancer burden because it aims to stop the disease before it starts or detect it at an early, more treatable stage. By preventing cancer, we not only save lives but also reduce the economic burden on families and society and improve the overall health and well-being of our communities.

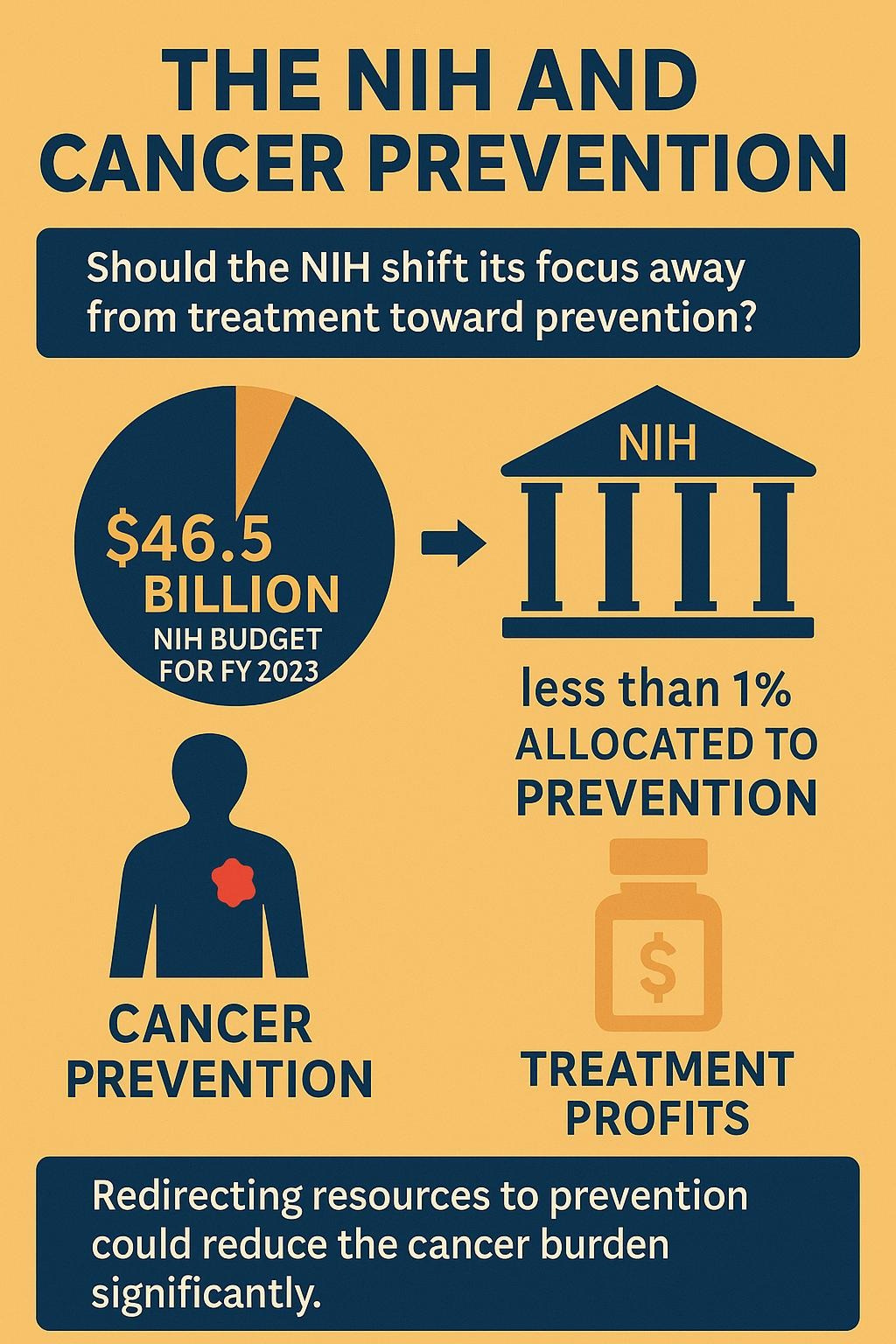

So, the question arises: Should the NIH redirect its resources toward prevention rather than treatment? This shift in focus, although it may challenge the interests of pharmaceutical companies, could be a game changer in our fight against cancer, as evident in radiology exams.

The NIH’s budget for fiscal year 2025 is approximately $46.5 billion, with the National Cancer Institute (NCI) receiving ~$7.9 billion for cancer research.

In 2023, only about 4% of NCI’s budget was allocated to prevention and early detection, despite estimates that 50% of cancers are preventable through lifestyle and environmental interventions. The majority (43.8%) went to Research Project Grants (RPGs), with 5,736 grants funded, including 1,369 competing grants, but prevention-specific grants are a small fraction. For example, programs like the Division of Cancer Prevention fund research in screening, interception, and symptom management, but these are dwarfed by treatment-focused initiatives.

It’s alarming that the NIH allocates a small portion of its substantial funding towards prevention. However, a shift in the NIH’s funding focus could significantly impact our ability to prevent cancer, offering a ray of hope in our fight against this disease. With increased investment and focus, we could see groundbreaking innovations and significant progress in cancer prevention research.

Treating is more profitable than prevention.

Drug companies profit more from treatments (e.g., a single immunotherapy course can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars) than from prevention. In 2023, oncology drugs generated $200 billion globally, per Statista. While the pharmaceutical industry doesn’t directly control the NIH, industry lobbying can influence policy, and drug trials often receive priority due to faster, tangible outcomes.

Systemic Challenges With Research Grants

Public health systems and research grants tend to focus on immediate, tangible outcomes. However, prevention, which requires long-term studies and behavioral changes, often gets deprioritized. It's crucial to remember that prevention-focused research has the potential to make a significant impact on our fight against cancer, offering hope for a healthier future.

Prevention strategies, especially primary prevention, take decades to show results. For example, smoking bans reduced lung cancer rates, but the impact took 20-30 years. NIH funding tends to favor quicker wins (e.g., new drugs) due to political and public pressure. It’s also important to note that a single NIH research grant can take years to write and develop, with no guarantee of winning the award. Therefore, for scientists to focus on grants that emphasize prevention is a risk. However, we must understand that the long-term benefits of prevention far outweigh the immediate gains of treatment.

Measurement difficulties

Proving the impact of prevention is more complex than proving the impact of treatment. A new drug’s effect is apparent in a 2-year trial, but preventing cancer through diet or environmental changes requires extensive, long-term studies. This makes prevention research less “sexy” for funding.

Primary prevention often relies on behavior and lifestyle changes (e.g., quitting smoking, reducing obesity), which face resistance. Only 8% of smokers successfully quit annually. A similar number of type 2 diabetics reverse their diabetes each year.

Science is in a “Dark Place”

The phrase resonates with ongoing issues like publication bias, replication crises, and the pressure to produce flashy results. These factors discourage researchers from tackling prevention, which often lacks the “breakthrough” appeal of new treatments. Other problems are preventing us from focusing on prevention. Surviving any cancer has an extremely high mortality rate, and almost no chemotherapies or radiation truly decrease mortality. Deaths directly caused by cancer treatments (treatment-related mortality, or TRM) are a critical and often underreported factor that can distort survival statistics. The Broken Science Institute has done a lot of research in this area.

The scientific journals are captured. Dr. Marcia Angell, who served as Editor-in-Chief of The New England Journal of Medicine for two decades, publicly acknowledged that journals have been captured by industry. Her exact words:

“It is simply no longer possible to believe much of the clinical research that is published or to rely on the judgment of trusted physicians or authoritative medical guidelines. I take no pleasure in this conclusion, which I reached slowly and reluctantly over my two decades as editor of The New England Journal of Medicine.”

Dr. Richard Horton, current editor-in-chief of The Lancet, admitted:

“The case against science is straightforward: much of the scientific literature, perhaps half, may simply be untrue. Afflicted by studies with small sample sizes, tiny effects, invalid exploratory analyses, and flagrant conflicts of interest, together with an obsession for pursuing fashionable trends of dubious importance, science has taken a turn towards darkness.”

Funding Bias: Most medical research funding, especially from private sectors such as pharmaceutical companies, tends to flow toward treatments because they offer quicker and more profitable returns. Developing drugs or therapies for existing conditions is often viewed as a safer bet than conducting long-term prevention studies, which are costly, time-consuming, and more challenging to quantify and evaluate. It’s challenging to place more emphasis on prevention when science is in a state of uncertainty, and most funding is directed toward treatment rather than prevention.

Where to go from here

No one has the right answer, but at a minimum we can start by aiming in a better direction. We need to start building bridges, not walls, between scientists, doctors, and the pharmaceutical companies. The Healing Science Policy Institute is trying to just that. If we genuinely want to win the war on cancer, we can’t keep showing up to the battlefield late. We must start upstream—before diagnosis, before pain, before loss—and build a system that values life not just in its final stages but from the very beginning.