My Lean Mass Hyper Responder Story

Recently, I’ve been writing about the Lean Mass Hyper-Responder (LMHR) phenomenon. I recently published an article about LMHR and LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) study by the Citizens Science Foundation that showed not everyone with high LDL-C develops atherosclerotic plaques. Next, I want to tell my own story. I’m a medical doctor, elite-level cyclist, tennis, enthusiast, father, and self-optimizer. My low-carb, high-fat diet (LCHF) journey began about 15 years ago. It started after a cycling accident, and I wanted to protect my brain from a traumatic brain injury using a ketogenic diet; I also was interested in how it would affect my cycling from an energy standpoint. One thing I noticed right away that it’s not far from a traditional French diet, and several articles written about the “French paradox.” At any given time, my ketones are usually in the nutritional ketosis range. And when I am gearing up for an event, I will add in some carbs as I race better when I do this. My friend, Peter Defty of Vespa OFM helped with this initial transition.

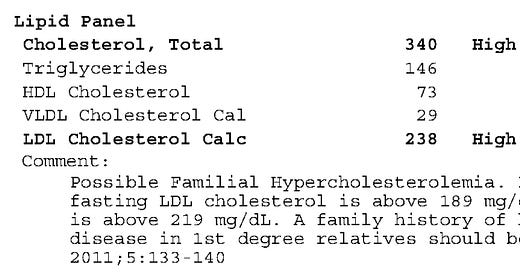

Shortly after living this low carb lifestyle, my cholesterol numbers spiked. Pre LCHF, my cholesterol numbers were normal in the low 100s. And afterwards, they spiked into the 200s.

I’ve had my LDL-C as 238mg/dl

I’ve had my LDL-C as low as 103 mg/dl

I was in the LMHR group even before Dave Feldman coined the term. I thrived on living this way, riding long distances without eating, my weight remained stable, and my focus was improved. However, I was concerned, like many, about what it could do to my heart and the rest of my body. I’ve learned from cardio-thoracic surgeons throughout the years that if you have cholesterol plaque buildup in one area, you have buildup in the other parts of your body, such as the carotid arteries and aorta; it’s important to remember that the human circulation extends about 60,000 miles. An interesting phenomenon is that veins never buildup atherosclerotic plaques (a story for another day.)

I’ve since learned everything possible about LCHF, with a particular emphasis on cholesterol, given my high lipid numbers. I started following Dave Feldman’s work, who recognized patterns in the lipid system similar to distributed objects in networks. I remember Dave presenting his work on shifting his cholesterol substantially without any medications or supplements, dropping his LDL cholesterol from the high 200s to less than 100 in days. The numbers were mind-blowing.

I’ve no preconceived notions that eating a high-fat diet could result in adverse health conditions. But as many people who follow LCHF, ketogenic, or carnivore diets, going to doctors who are clueless about these lifestyles is likely to be counterproductive. So, I have several yearly blood tests, checking my inflammatory markers, lipid profiles, and hormones. I also undergo echocardiograms, ECGs, carotid ultrasounds, and cardiac stress tests (video). It’s not because I’m going to have a cardiac event anytime soon, rather I’m genuinely interested in the numbers and to see how my lifestyle affects my physiology, not just for myself but for my wife and daughter.

Life Changing Events

In 2021, I experienced COVID. For treatment, I employed the kitchen sink method, including medications, vitamin IVs, and sauna. I took thymosin-alpha peptides, pentoxifylline, ortho immune, which contained vitamin C curcumin, and zinc. I also used my hyperbaric chamber daily and ensured I got plenty of sunlight. I also took vitamin D supplements. The infection wasn’t bad, but the ensuing pneumonia lasted a couple of weeks.

I started feeling better and was eager to resume light exercise. I laced up my jogging shoes and went out for a run. After a 10-minute warm up, I started running at an easy pace using only my perceptions which was about an 8 to 9 minute per-mile pace. I describe running by perception or feel in The Science of the Marathon. Some minutes later, I experienced a foreign chest pressure that enveloped my entire chest, it was if an elephant was sitting on me. Immediately, “this is what a heart attack must feel like.” Skeptical, I thought it must be acid-reflux. But I knew this was more than indigestion as the chest pressure was significant and uncomfortable. The discomfort resided after resting some minutes. So, I began running again, and minutes later, the same chest pressure returned. It takes the brain minutes to register the reality, but there was no mistake about what I was experiencing and how it increased with exercise intensity, even if the level of exercise intensity was minimal for what I am used to. I tried jogging one last time, and the same result. Dejected, I walked home with the reality that I may be having a heart attack.

At home, I immediately checked my ECG on my handheld Kardia device. I understand this is a cursory device, but it showed no abnormalities, such as ST elevation or tachycardia. At rest, I felt comfortable, so I decided, wisely or not, to stay home and resume testing the following day. I did take an aspirin and Plavix. The next day, I got a CAC test, ECG, lab testing, and heart echocardiogram. To my amazement, everything was normal. Unsure of what I was experiencing, I spoke with a cardiologist colleague, and he agreed that since everything was normal, I could rest and retest later, and I would probably be fine. Since all my tests were normal, I treated the situation as if I had myocarditis. I started a regimen of colchicine, NSAIDs, no intense exercise, and steroids. I continued sauna, hyperbaric oxygen just about every day. I also continued the vitamin IVs and peptides.

A week later, I visited my cardiologist, and he knows that I eat LCHF, mostly carnivore, and have kept the same weight since high school. He disagrees with my diet but understands that I’m in excellent shape. We repeated the heart echocardiogram, ECG, cardiac stress test, and lab tests. We found a slight change in my EKG, but nothing significant. He cleared me and said it might have been a sub-acute case of myocarditis or atypical chest pain and said I could go back to light exercise and watch my diet. I thought about it. “No,” I said to myself. I requested that we do the gold standard test, a heart catheterization, to see what was going on inside of my heart and coronary arteries. This was a strange and uncomfortable scenario since I’ve been a life-long endurance athlete. I have no misconceptions that years of cycling, running, and sustained high heart rates can be harmful to the heart. Born to Run by Christopher McDougall is a great book highlighting the potential harms of chronic endurance exercise. My cardiologist agreed given my history, the intensity of the chest pain, and how it was related to exercise. I wanted to do everything to rule out the cause of my chest pain, not just for myself, but for my young daughter. I was ready for the truth of whatever was going on and act accordingly to have the best possible future for myself and my family.

Cath Lab

At the hospital pre-op area, they prepped me for a heart catheterization with the possibility of a stent. My cardiologist told me, Johnathan, “I’m pretty sure you’ll have something, given your high cholesterol and LDLs.” At this point, I just wanted the truth. I received no sedation during the procedure and only local anesthesia on my skin for the catheter that went into my radial artery. The cardiologist fished the catheter through the artery into my heart, I could feel the line bouncing; it was mildly uncomfortable but nothing too alarming. I watched the screen intently as the dye was injected. My coronaries were wide open. The cardiologist studied the screen closely and then looked at me in disbelief saying, “I don’t believe this picture. I want to repeat it.” I told him to go ahead, with little emotion. He repeated the dye injection, and my coronary vasculature lit up like a Christmas tree. I could see the look on my cardiologist’s face as he shook his head in disbelief. He carefully reviewed the replay of the dye going through my coronary vessels. Finally, he looked at me and said Johnathan, “not only do you have no coronary plaques, you don’t even have age-appropriate plaques.” Then he checked my valve pressures and noted they were consistent with my athletic heart. I knew that my cardiologist was happy for me, but at the same time, he was dismayed by the results. He must have been thinking about my several years of living with high cholesterol and years of exercise.

So, there it was. I performed the gold standard test to rule out if I had any heart pathology. I was relieved for many reasons. The biggest reason for relief was that I would be around for my family and not die from a heart attack. I was also happy about confirming eating a non-processed, low-carb, mostly carnivore diet could be heart-healthy, as I already knew it was optimal for my health. I was ecstatic that I could return to normal exercise.

My cardiologist and I had a long meeting after the test, and I pressed him as to what could have caused my chest pain. He said it wasn’t due to any plaque as there was none to speak of, not even a non-calcified plaque that could have broken off and caused such an event. He agreed the chest pain was too severe and related to exercise to be chest pain from indigestion. He reluctantly agreed that I probably experienced a case of what’s called subacute myocarditis after a viral infection, which in this case was COVID-19. I have never gotten a cardiac MRI to confirm the diagnosis.

After the heart catheterization, I continued my protocol, and then I reintroduced exercise after about 6 weeks. I was going crazy not being able to cycle or play tennis. Eventually, I built up to the level of exercise I was accustomed to and have been good ever since.

Disclaimer: This article aims to show that, like the LHMR study, not all high cholesterol leads to atherosclerotic plaques. It’s also not to prove anyone wrong about how I live or suggest that anyone should live as I do, assuming they will have the same results. It’s about showing the world that complex things are complex. A reductionist approach to anything, myocarditis, heart disease, and many of the things that ail us as human beings are complex and need to be figured out, and perhaps having a little faith that what you’re doing will be for the greater good.